The author conducting research on recreational anglers on Galata Bridge, in the Golden Horn estuary of Istanbul (© A. Ulman)

by Aylin Ulman

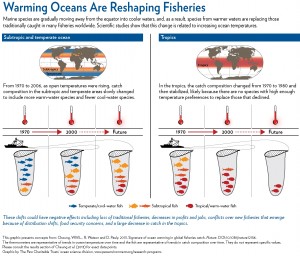

In 2011, I began working for the Sea Around Us Project to complete catch reconstructions for Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea countries. I quickly realized, while studying Turkey’s fisheries, that some marine ecosystems of Turkey recently underwent immense reductions of commercial species [1], leading to entire trophic shifts, but little data were available to explain these issues. At the beginning of my MSc with Daniel Pauly in 2012, it was decided that I’d go to Turkey to document the shifting baselines syndrome, i.e., gradual shifts in perception of the ecosystem, and collect details on these missing species/habitats.

My father was part of this study, as he is part of the first generation of scuba divers from Istanbul in the late 1950s and remembers a time long gone-by, when the Bosphorus was pristine and teeming with marine life. He has always been a typical eastern Mediterranean fisher, which does not normally go well with proud marine conservationists such as me. However, documenting shifting baselines in Turkey allowed me to turn his older generation’s Turkish traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) into recording the missing pieces of biological history.

To assess the shifting baselines syndrome, I compared today’s level of fishing effort, catch amounts, catch composition, and mean sizes to the time when these fisheries began; had them rate the quality of fishing now and when they first started; asked about any local extirpations or serious collapses in fish abundances; asked about the changes in catch of several other key taxa; and then queried the fishers about how they would improve fisheries.

The present plight of Turkish fisheries are likely a combination of the following: they have a tremendous fishing fleet (over 17,000 commercial vessels), very sophisticated technology (i.e., sonars and GPS), no catch restrictions, little enforcement of regulations, and also grapple with pollution issues.

I attended meetings for both the small-scale and industrial sectors and quickly realized that some sectors were more affected by the changes in biodiversity and catches than others. Consequently, I decided to interview fishers from all sectors (industrial, artisanal, and recreational) to understand their unique perspectives. Thanks to my prior work with the Sea Around Us, I knew over 100 Turkish names for fish, which was essential in conducting my surveys. I concentrated mostly on the Istanbul Bosphorus (where fishers depart to fish each of Turkey’s four seas), the Dardanelles (home to the most productive migration route for the key pelagic species), and the southwestern peninsula (which separates the Aegean Sea from the Mediterranean).

I first began my survey training on my father’s fishing friends in Datça, on the very southwestern peninsula, where he is the vice-president of the local fisheries co-operative. Everywhere, fishers were very open and helpful to me, which surprised me. Many were asking me: “Why does our government not try to learn how our seas have changed, yet a Canadian is out there with us trying to understand it?” I then realized just how privileged we are to be able to conduct this type of study. I was most surprised by how welcomed I was by the industrial fishers. I had gone there with a preconceived notion that these were the bad guys, wielding an immense fishing power. However, I quickly learned that these were the true ‘traditional’ fishers of the country, many whose families had been fishing for hundreds of years. They really care about the future of the fisheries and are desperately seeking some sort of output control to manage the stocks.

As I surveyed each fishing sector, and made many new friends, I gained new insights into a few common illegal fisheries of the Bosphorus, like the sea snail, Mediterranean mussel and bottom trawl fisheries, and now I have numbers to better estimate them.

I realized that the rate of ecological change is unbelievable for certain areas. For example, the Golden Horn estuary of the Bosphorus was teeming with swordfish, bluefin tuna, lobsters and Atlantic mackerel just 60 years ago, all of which seem to have vanished since the 1970s. Older fishers rarely bring up these species in conversation anymore, but are still haunted by their disappearances.

If I had to remember just a few quotes from this field trip, they would be:

-“Forget about making money [fishing], we do not even enjoy this anymore”;

-“30 years ago, 3 months of fishing would leave your pockets full for the other 9 months, now we fish every day and can barely afford our bread”;

-“Both small-scale and medium-scale fisheries are just not viable anymore, only the large-scale fisheries can survive, we need to find other work to complement our fishing salaries”; and

-“We have seen the best fishing years imaginable, but our children will only know those years through encyclopedias”.

On a side note, I was staying in Taksim Square when I was in Istanbul, where east meets west, and ancient history is met with modernity. There, I got to witness the Turkish national revolution, and its daily progression first hand. Its early stages were a very elated street party, comparable in my lifetime only to the Toronto after the Blue Jay’s World Series wins of 1992 and 1993. The educated half of the country united for the first time in history in Taksim Square to oppose actions of the Prime Minister. The protesters went from feeling utterly powerless to realizing that united they were strong, and that the world indeed was listening (for a little while anyways). I have never felt more proud to be Turkish, that is, until they began to use tear gas; I then realized that human rights and democracy have a different meaning than in Canada, and that it was better to be safe than arrested…

The shifted baselines of Turkey had not been previously studied. There is no other way to find out this information besides speaking to the fishers whom have witnessed these changes first hand. I hope to make my findings accessible to the fishing community in their local publications so that those without the prior ecological knowledge can at least try to imagine it, and even pass it down. Now that we know that Turkish citizens have a voice, it is now time for Turkish fishers to have a voice.

References

Ulman A, Bekişoğlu Ş, Zengin M, Knudsen S, Ünal V, Mathews C, Harper S, Zeller D and Pauly D (2013) From bonito to anchovy: a reconstruction of Turkey’s marine fisheries catches (1950-2010). Mediterranean Marine Science 14(2): 309-342.