This article was written by research assistant, Sarah Harper, and appears in the July/August 2011 newsletter.

This article was written by research assistant, Sarah Harper, and appears in the July/August 2011 newsletter.

The Sea Around Us project and Oceana team up for a conference to discuss what’s at risk, from a marine biodiversity perspective, if plans go ahead to drill for oil off the coast of Belize. The conference, co-hosted by Daniel Pauly and Deng Palomares, held in Belize City on June 29 and 30th was entitled Too precious to drill: the marine biodiversity of Belize. At the conference marine biologists, taxonomists and economists provided an exhaustive list of reasons the precious and pristine marine environment of Belize could be at risk. With some of the healthiest coral reefs, manatee populations, shark diversity and reef fish spawning aggregations in the Caribbean, Belize would lose a lot from an oil spill1. Tourism and fisheries are particularly at risk as these both rely on a healthy marine environment, and provide jobs, revenue and food to the people of Belize.

Just over a year ago, the International NGO Oceana, which recently opened an office in Belize City, caught wind of plans to develop an offshore oil industry in Belize. Leaked govermnment documents revealed a map of the territorial waters of Belize, a checkerboard of oil exploration consessions. Oceana, the largest international NGO focused solely on ocean conservation, raised the alarm bell and decided that quick action was needed to engage and empower the people of Belize to stand up to the government and protect their precious natural wealth. A campaign was launched with a petition to be signed by the people of Belize demanding a referendum on oil exploration offshore and in protected areas. Oceana met their target with over 10% of the voting population signing the petition (17,000+ signatures), the minimum requirement for a referendum to be called, and continues to raise awareness throughout the country with their colourful campaign bus (see photo) and heavy media engagements.

Further to their in-country efforts to engage the public, Oceana teamed up with the Sea Around Us project to deliver the scientific evidence required for a strong case against offshore drilling in Belize. A conference was set for the end of June 2011 and international scientists selected to share their expertise, including Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Dirk Zeller and myself. One of the goals of the conference was to repatriate the knowledge and expertise that had been gleaned from years of scientific study within Belize but that had not necessarily stayed within its borders. Many detailed studies have been conducted on diverse aspects of the Belizean marine environment but have been published abroad. The conference aimed to bring this knowledge back to Belize and use it as a tool to inform and improve decision-making.

Attendance at the two-day conference included fishers, government deligates, the US embasador to Belize, media, NGO’s and citizens of Belize. While the conference was well-attended, the main outlet for disseminating this information to the general public was the media, via breakfast television shows, radio, talk shows, etc.

The conference concluded with a letter to the government of Belize signed by 20 scientists from 10 ten nationaltities and most with years of experience studying the marine environment of Belize. This professional statement re-iterated the importance and value of the marine evironment and the need to protect it from anthropogenic threats, offshore oil drilling in particular.

With the conference concluded, a scientific report just released and a flurry of media exposure, the question remains: to drill or not to drill? The hope is that the government wakes up to an informed public who are now asking the tough questions: who will benefit from offshore oil drilling? Who will pay the price for the high environmental costs associated with this industry?

Perhaps I am biased given my background in marine conservation, but I think that in the waters of Belize, drilling for oil just doesn’t make sense! On the last day of the conference, the scientists and media adventured offshore to Turneffe Atoll, a typical reef for this area known for its excellent diving, snorkeling and sportfishing opportunities. We stopped for lunch at a lodge nestled in amongst the mangroves linning the atoll and heard about the decade long struggle to get the Atoll designated as a marine reserve in order to better preserve its natural beauty. Unfortunately, this Atoll lies within the largest of the oil consessions own by Princess Petroleum Ltd. and likely one of the first areas to be drilled. This Atoll alone brings in 40 million USD annually from flyfishing for bonefish, tarpon and permit. This is money that goes directly into the Belizean economy and to the people of Belize. Conversely, the majority of oil revenue from drilling in the waters adjacent to this popular fishing hole would go mainly to the international investors of the oil companies. Simply looking at the economic picture, drilling for oil would likely not improve the economic situation in Belize and the risk in terms of losses both in fisheries and tourism are huge.

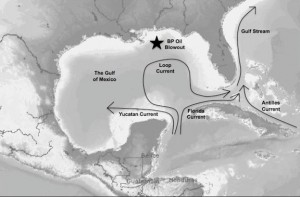

On the biological side, Belize also stands to lose a lot. The conference highlighted over 2,000 marine species of fish, invertebrate and plants, found in the waters of Belize and now documented in FishBase and SeaLifeBase. I was able to experience first hand some of this incredible diversity and abundance of life with a snorkel through the reef at Hol Chan marine reserve, not far from Turneffe Atoll. A glance around the marine reserve revealed a tremendous array of sharks, rays, turtles, reef fish, dolphins, corals, and much more. Belize has arguably the healthiest Antillean manatee population in the world and still has relatively abundant shark populations, including whale sharks. Looking around as I snorkeled through the reef, I could see that an oil spill in the waters of Belize would have an incredibly devastating effect. A catastrophic oil spill, given recent events in the Gulf of Mexico and other parts of the world, is quite possible. Drilling for oil offshore is much riskier than onshore, and in a biologically rich and diverse marine environment such as Belize, the risks are too high—in my opinion. An oil spill could wipe everything out and Belize would be left with nothing-no tourism, no fishing!

Throughout the conference, Audrey-Matura Sheppard, VP of Oceana Belize, emphasized the importance of the reef in providing food security and jobs, “Think about Belize without the reef? Where would we be without that?”. The Belize barrier reef, the largest barrier reef system in the northern hemisphere and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a sense of national pride, a source of livelihoods, food security and jobs for the people of Belize. That is definitely worth protecting!

For more information about marine biodiversity in Belize, the conference and its outputs, visit this website.

1 McCrea-Strub, A. and Pauly, D. (2011) Oil and fisheries in the Gulf of Mexico. Ocean and Coastal Law Journal [in press].