At the end of August, I moved to Vancouver from Sanibel Island, Florida. Sanibel is a tiny island in the Gulf of Mexico, where millions of gallons of oil have spilled since the Deepwater Horizon explosion on April 20, 2010. When people learn that I am from the Gulf region, they usually ask how much oil I saw on nearby beaches. Surprisingly, the answer is none.

At the end of August, I moved to Vancouver from Sanibel Island, Florida. Sanibel is a tiny island in the Gulf of Mexico, where millions of gallons of oil have spilled since the Deepwater Horizon explosion on April 20, 2010. When people learn that I am from the Gulf region, they usually ask how much oil I saw on nearby beaches. Surprisingly, the answer is none.

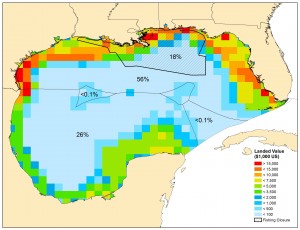

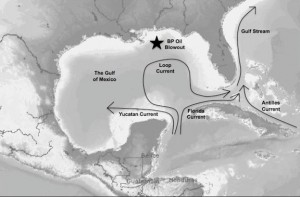

Oil has washed ashore in the northern region of the Gulf, closer to the spill, but southern Florida’s coast appears largely oil-free. The absence of visible oil in southwest Florida is probably due to a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors. The Loop Current flows relatively far offshore, so it has not played a significant part in carrying oil or tarballs to SW Florida’s coastal areas (see figure). Also, major storms with the potential to push oil inland have bypassed the area so far this hurricane season.

Despite the pristine beach conditions in SW Florida, it is important to remember that the lack of visible oil does not necessarily indicate a lack of presence. Chemical dispersants played a key role in hiding surface oil that might otherwise have washed up on beaches today.

Dispersants are chemicals that break oil into small droplets, which are then distributed throughout the water column by wave action and currents. Dispersants do not clean up or get rid of the oil – they simply spread it out. In July alone, the US dropped one third of the world’s supply of dispersants into the Gulf of Mexico, effectively making the oil difficult to find.

You can compare the use of dispersants to a common scenario that most everyone experienced as a child – hiding a mess from your parents. Your mom is angry about the messy state of your room, so she tells you to clean it up. Instead of cleaning up the right way – putting each item where it belongs – you shove everything under the bed, hiding the problem. By using dispersants, the responsible parties were hiding the oil spill instead of cleaning it up.

Hiding the mess is an attractive temporary solution, but the problem becomes apparent when your mom looks under the bed. Now you are in big trouble. The consequences are much worse than if you had just initially taken the responsibility and time to clean up correctly.

A recent study of core samples taken from multiple locations in the Gulf revealed as much as a 5 cm layer of oil on top of the normal bottom sediments. Samantha Joye, a professor from the University of Georgia who collected the core samples, said in an interview with NPR, “The sheer coverage here is leading us all to come to the conclusion that it has to be sedimented oil from the oil spill, because it’s all over the place.” (http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId= 129782098&ps=cprs)

Using dispersants to hide the oil was a fast and easy way to maximize the number of clean beaches and keep the general public happy by making the unpleasant effects of the oil spill appear to go away. However, the long-term environmental and ecological effects of spreading oil throughout the water column are unknown. The Obama administration’s leader of the scientific response to the oil spill, Marcia McNutt, admitted last week that the government decided to use dispersants without prior knowledge of the potential environmental effects, saying “there was no science when you apply [chemical dispersants] in the deep sea — we didn’t know the impacts on sea life.”She also acknowledged that it may be years before we know the full impact of the decision (http://www.poptech.org/blog/marcia_mcnutt_ on_uncertainty_in_the_flow).There is a strong chance that the combination of oil and chemical ingredients in the dispersants will have harmful effects on marine life and potentially the humans who choose to consume that seafood in the near future.

Naturally, oil floats on the surface. This makes it possible (although very difficult) to clean up. Sending oil to the bottom of the ocean makes it virtually impossible to remove. It also damages sea grass beds and coral reefs, and the oil is inadvertently consumed by mussels and other filter feeders – many of which make up the base of the Gulf food web. The chemicals in the oil (mixed with the mysterious chemicals in the dispersants) could accumulate up the food chain over time until high levels are found in commonly-consumed species. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is monitoring seafood from the Gulf of Mexico carefully, and a number of independent studies are in progress.

The long-term effects of dispersants in the Gulf of Mexico are unclear at this point. The Gulf is one of the world’s top food-producing regions, so dispersants could have huge implications for fisheries. Thanks to dispersants, people in southwest Florida can enjoy the beaches now, but they may not be able to enjoy local seafood safely in the years to come.

Figure: Major currents in the Gulf of Mexico. Near SW Florida, the Loop Current flows far enough offshore that it has not carried oil to beaches.

This article is written by Sea Around Us M.Sc. student Leah Biery