Join the Sea Around Us and many of our collaborators at the International Marine Conservation Congress, May 14-18, 2011 in Victoria, BC. Find a few of our specific presentations below.

Join the Sea Around Us and many of our collaborators at the International Marine Conservation Congress, May 14-18, 2011 in Victoria, BC. Find a few of our specific presentations below.

Sunday, May 15

10:15am (15 minutes)

Sarah Harper The fisheries of small island countries

11:05am (5 minutes)

Leah Biery Estimating the Global Distribution and Species Composition of the Shark Fin Supply from the Bottom Up

11:10am (5 minutes)

Rhona Govender Small but Mighty: the Real Contribution of Small-scale Fisheries to Global Catch

2:30pm (15 minutes)

Ashley Strub Global financial investment in marine protected areas

2:45pm (15 minutes)

Daniel Pauly Big reserves are better

4:50 (5 minutes)

Mark Hemmings Changes in Maldivian Fisheries

4:45pm (15 minutes)

Colette Wabnitz The ecological role of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in Hawaiian and Caribbean marine ecosystems and implications for conservation

6pm (5 minutes)

Megan Bailey Do Europe’s Reduction Fisheries Contribute to Sustainability?

Monday, May 16

10:30am (15 minutes)

Vicky Lam Climate change and the economics of global fisheries

10:45am (15 minutes)

William Cheung Global changes in body size, distribution and productivity of marine fishes under climate change: implications for conservation

6:15pm (15 minutes)

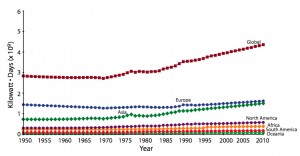

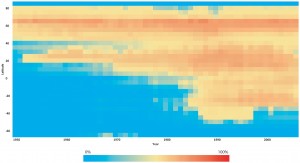

Daniel Pauly (on behalf of Wilf Swartz) The spatial expansion of the world’s marine fisheries: 1950 to present

Tuesday, May 17

10:45am (15 minutes)

Michelle Paleczny Are global marine fisheries starving seabirds?

11am (15 minutes)

Marta Coll Spatial overlap between marine biodiversity, cumulative threats and marine reserves in the Mediterranean Sea

2:15pm (15 minutes)

Jennifer Jacquet Public vs. Personal Impressions of the Gulf Oil Spill

2:45pm (15 minutes)

Ashley McCrae-Strub Oil and fisheries in the Gulf of Mexico: potential impacts on catch

3pm (15 minutes)

Kristin Kleisner (on behalf of Rashid Sumaila) Impact of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the economics of U.S. Gulf fisheries

5pm (15 minutes)

Dirk Zeller Arctic fisheries catches in Russia, USA and Canada: Baselines for neglected ecosystems

5pm (15 minutes)

Frederic LeManach Magnitude of missing catches in official fisheries statistics and implications for the local population – the example of Madagascar

Wednesday, May 18

10:15 (15 minutes)

Jennifer Jacquet Intimacy through the Internet: Why Conservation Needs the Web

10:15 (15 minutes)

Sarika Cullis-Suzuki Regional fisheries management organizations: effectiveness and accountability on the high seas

10:45 (15 minutes)

Pablo Trujillo See-Food from Space

11:30 (15 minutes)

Kristin Kleisner Exploring indicators of fishing pressures in the context of the OHI with a focus on correcting the Marine Trophic Index for geographic expansion

3:30pm (15 minutes)

Dalal Al-Abdulrazzak Gaining Perspective on What We’ve Lost