by Lucas Brotz

Lucas Brotz (right) helps DFO crew aboard the CCGS W.E. Ricker sort the catch of the day: juvenile salmon and lion’s mane jellyfish.

As their name suggests, leatherbacks do not have a hard shell like the other six species of sea turtles alive today. Rather, their shell consists of smooth, leathery skin with seven ridges running its length. Such reptiles first appeared in the fossil record about 100 million years ago when their family branched off from other hard-shelled turtles, underlining the fact that these are truly ancient mariners. Leatherbacks are massive creatures. They frequently grow to hundreds of kilograms and can potentially surpass a tonne. From tip to tail the largest exceed three meters, with their flippers spanning more than four meters.

The leatherback’s list of superlatives is nearly as large as the animals themselves! Among reptiles they are the fastest growing, fastest moving, and except for a few crocodiles, the heaviest. They are also among the most widely distributed animals in the world, mainly due to migrations that put all but a few marine mammals and bird species to shame. Surprisingly, they are also warm-blooded, and are therefore able to survive in environments far beyond the reach of their cold-blooded relatives. Believe it or not, leatherbacks have been sighted north of the Arctic Circle! To top this off, leatherbacks have been recorded diving deeper than a kilometer, plunging further into the abyss than almost all other air-breathers.

But perhaps the most astounding fact about this fascinating species (although I will admit, I am biased) is that leatherbacks can grow so large, travel so far and dive so deep on a diet consisting almost exclusively of jellyfish!

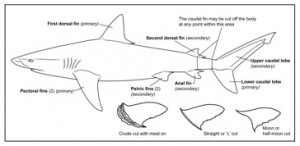

Why is this surprising? Jellyfish are roughly 95% water, therefore obtaining sufficient nutrition from them requires some serious feasting. A leatherback can consume hundreds of kilograms of jellyfish in a single day, which not only appears to supply all of their energetic demands, but also allows them to fatten up for return migrations to breeding areas. Part of the success of such a strategy relies on the fact that jellyfish often occur in dense aggregations known as blooms. In addition, jellyfish have virtually no escape response, especially from an animal as fast and maneuverable as a sea turtle. Therefore, locating dense blooms of jellies is likely key for leatherback feeding success and appears to be the sole reason why they embark on vast migrations from breeding areas in the tropics to more temperate areas, including Canadian waters.

So now you can understand why someone who studies jellyfish would receive an e-mail about endangered sea turtles. And endangered they are. While there are a number of reasons for optimism regarding leatherbacks in the Atlantic, the Pacific populations appear to be on an alarming trajectory. Their numbers are uncertain, but it is estimated that there are fewer than 3,000 nesting females left – a precipitous crash of more than 97% in only a few decades. Numbers continue to decline, and Pacific leatherbacks appear dangerously close to extinction.

As one might imagine, sightings of leatherbacks in Canadian Pacific waters are relatively rare, averaging only about one per year. While that is not a lot, members of the population do visit here. And in order to survive unthinkable migrations from remote breeding sites in Indonesia and the Solomon Islands, those turtles visiting Canada’s west coast are likely the largest and heartiest of the population. Therefore helping or saving just a few of these individuals could be crucial for a subpopulation’s survival. The areas used by leatherbacks to feed on jellyfish blooms in British Columbia represent critical habitat, but unfortunately we know relatively little about the jellyfish living in Canadian waters. Migrating leatherbacks are likely feasting on an abundance of large “true jellyfish” (class Scyphozoa), including lion’s mane jellies (Cyanea capillata), sea nettles (Chrysaora fuscescens) and moon jellies (Aurelia labiata). In order to better understand the abundance and distribution of these species, I began working with Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) scientists and technicians.

Interestingly, most of the scientists I worked with are salmon specialists. This is mainly because salmon scientists possess one thing that pretty much all marine biologists and oceanographers covet: ship time. DFO crews conduct integrated ecosystem surveys several times each year in the coastal waters of British Columbia and have implemented consistent sampling methods since 1998. These sustained, year-round surveys along repeat transects are a rarity in an age of funding cuts, and the resultant datasets provide a wealth of valuable information. In addition to collecting oceanographic data, these surveys involve tows using large trawl nets to collect and study juvenile salmon populations. The unwanted by-catch in these trawls can include large jellyfish. Properly identifying and monitoring these jellyfish catches could provide new and valuable insights into these organisms in our coastal waters. This information may also be indispensable, I believe, for understanding the relationship between critically endangered leatherbacks and their gelatinous prey.

All of the scientists I worked with recognized the importance of collecting such information, and together we developed a procedure that we hope will create a permanent record of all future jellyfish catch. While I was eager to convince those I collaborated with to gather as much data as possible, I had to keep in mind that jellyfish were not the focus of the surveys and any procedure too onerous was unlikely to be adopted. Therefore, the protocol was designed to minimize the effort required for jellyfish processing, while at the same time maximizing the amount of useful information collected. In addition, a step-wise approach to jellyfish monitoring was recommended, whereby scientists and technicians can collect a minimum amount of data on jellyfish if they are analysing other catch, or obtain more detailed information if processing time allows. Thanks to this collaboration between DFO, SARA recovery planners and the Fisheries Centre, we should be able to rapidly increase our understanding of jellyfish in coastal waters in the coming years, as well as identify those regions that might be most important for foraging leatherbacks.

While eating jellyfish appears to have been a successful strategy for leatherbacks for millions of years, there are disadvantages to having a gelatinous diet in the contemporary world. Plastic debris, which now litters the oceans, often looks very much like jellyfish. Studies have found more than a third of examined leatherbacks have plastic in their intestines and the proportion for dead leatherbacks is double that. But perhaps the largest threat to leatherbacks is as a result of their trans-oceanic migrations between breeding and feeding areas. These epic journeys bring leatherbacks into repeated contact with the ocean’s most fearsome predator – humans. Leatherbacks are frequently caught as unintended by-catch or become entangled in the miles of fishing gear that crisscross the oceans. Anything that prevents turtles, which are air-breathers, from reaching the surface will cause death in less than an hour. Compound these dangers with poaching for turtle meat and eggs, global warming and an overall lack of awareness about the problems, and you start to read the Pacific leatherback’s epitaph.

An individual leatherback endures what seems like a life of hardship – swimming thousands of miles across oceans of hazards, only to have cold, stinging jellyfish for breakfast, lunch and dinner. As a species, leatherbacks have persevered through unimaginable times, including ice ages and major extinctions. In fact, they are often referred to as Earth’s last dinosaur. But it seems that leatherbacks may have finally met their match during this era dominated by the human species. I find it especially tragic to see such a charismatic animal that has survived for so long pushed to the brink of extinction in only a few decades. I have yet to be lucky enough to look into the eyes of a wild Pacific leatherback, something I long to do. I only hope that such an experience will remain a possibility.

References

Benson SR, Dutton PH, Hitipeuw C, Samber B, Bakarbessy J and Parker D (2007) Post-nesting migrations of leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) from Jamursba-Medi, Bird’s Head Peninsula, Indonesia. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6: 150-154.

Brotz L, Cheung WWL, Kleisner K, Pakhomov E and Pauly D (2012) Increasing jellyfish populations: trends in large marine ecosystems. Hydrobiologia 690: 3-20.

Heaslip SG, Iverson SJ, Bowen WD and James MC (2012). Jellyfish support high energy intake of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea): video evidence from animal-borne cameras. PLoS ONE 7: e33259.

Mrosovsky N, Ryan GD and James MC (2009) Leatherback turtles: the menace of plastic. Marine Pollution Bulletin 58: 287-289.

Safina C (2006) Voyage of the Turtle. Holt, New York. 383 pp.

Spotila JR, Reina RD, Steyermark AC, Plotkin PT and Paladino FV (2000) Pacific leatherback turtles face extinction. Nature 405: 529-530.